Posted by Chandni Patel, policy and research officer at Legal Futures Associate, the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives

Patel: Will these two models of categorisation remain sufficient?

AI, blockchain, Big Data, cloud computing, smart contracts, etc. How can practitioners best assess the various digital solutions for providing legal services?

From Law Commission consultations on the electronic execution of documents to government-wide projects such as HM Courts & Tribunals’ court modernisation programme and HM Land Registry’s Digital Street, it is no secret that digitisation and technology-based solutions are permeating every corner of legal services and our justice system.

The backdrop

The discourse on this topic is vast. There are technologies that are already available or entering the market and technology solutions that are still in research and development seeking to become available in the not-so-distant future.

At the other end of the spectrum – where truly disruptive and often ethically complex ideas emerge – are concepts such as robot judges and predictive algorithms, for which it is difficult to attribute a timescale.

Against this backdrop, it can be difficult to navigate your way around the tech landscape, let alone assess the risks and opportunities posed to the future of legal regulation, the internal workings of law firms and the equilibrium of supply and demand at a time of great unmet legal need.

In unpicking these wider questions, this article seeks to highlight two different models that have been developed for grouping technologies – and the questions that should be considered under each – to help future-proof your technology solutions.

Model 1: LegalTech v LawTech

The first model that emerged on the scene was the distinction between LegalTech and LawTech. Although criticised by some as a false dichotomy due to its over-simplistic approach when applied to policy making, this distinction can be useful for practitioners.

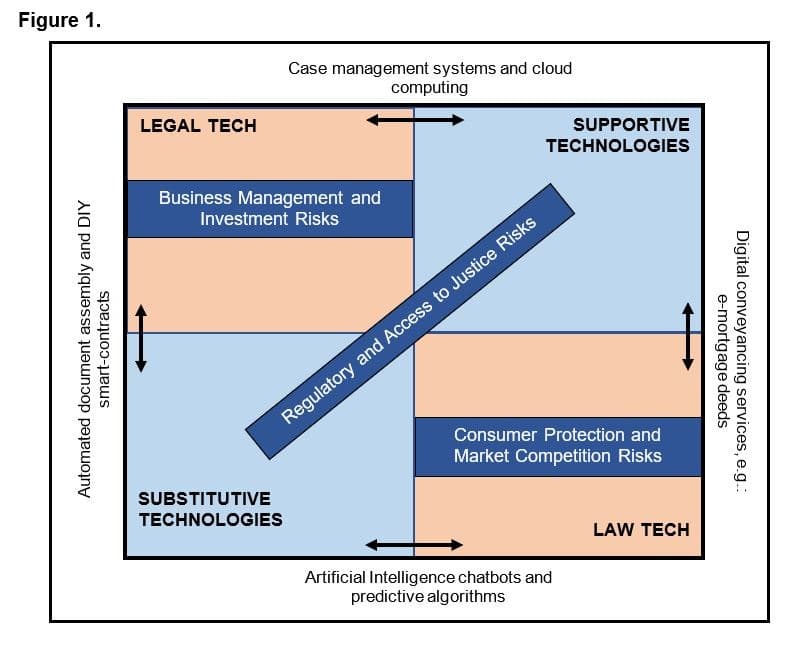

Under this model, LegalTech can be distinguished as assistive technology that aids legal service providers in the automation of internal processes and case management. LawTech, by contrast, seeks to help consumers interact directly with legal services either through enhanced client experience or self-service/DIY-law.

In other words, this dichotomy can be reframed as a question of whether the technology in question operates, fundamentally, on a business-to-business level, where the primary user is a legal service provider (ie, LegalTech) or a business-to-consumer level (ie, LawTech). As such, the primary focus of this model rests on the identity of the end-user.

Whilst this distinction may seem artificial or arbitrary, it can be useful to consider new technologies from the lens of the end-user, as the risks and sensitivities involved will naturally differ.

For instance, the risks involved in LegalTech are predominantly internal, centring around business-management considerations. Critical questions to ask will, therefore, focus on topics such as interoperability, cost-benefits, implementation strategies, training, GDPR and corporate compliance, to name a few.

However, the risks involved in LawTech are wider reaching owing to its consumer-facing nature. This is no doubt in part why these sorts of technologies are still at the early stages of development and use. The critical questions here focus on much broader topics, such as accessibility, consumer protection standards, marketing, consumer choice, competition and transparency.

This is not to say that these risks are mutually exclusive, but to emphasise that in identifying different technology, asking yourself whom it is targeted towards can be a helpful starting point for analysing prospective technology solutions.

Model 2: Supportive technologies v Substitutive technologies

A second model – coined by Professor Stephen Mayson in his review of legal regulation – distinguishes technology based on whether it is supportive, “in the sense that it supports providers of legal services either in the delivery of a legal activity”, or substitutive, in that it “does not simply support individual or institutional providers of legal services but actually substitutes for them… with no necessary human involvement at the point of delivery”.

At first glance, this may seem similar to the LawTech/LegalTech dichotomy; however, this distinction is more concerned with who or what is delivering legal services through new technologies, as opposed to who is using the technology-based solutions.

Through this lens, risks and opportunities are measured differently, focusing instead on how new technology might disrupt the supply chain.

The questions to be asked depend upon the levels of separation that new technologies create between existing legal services providers and the consumer, along with the opportunities and risks that could emerge from the resulting gap.

For instance, if the technology at hand devolves the provision of legal services to a third-party intermediary or to the technology itself, questions around authorisation, regulatory risk, compliance standards, liability and how to maintain high-quality justice outcomes start to emerge.

Confronted with this level of separation in delivery, law firms and legal practitioners need to be sensitive to the wider implications that substitutive technologies, and supportive technologies (where legal services have been outsourced to a third party) could have on internal hiring and recruitment practices, due diligence checks and supply chain management.

In turn, the identity of the provider of technology-based solutions becomes more important than that of the end-user.

Central to this delivery-based model are the risks posed at a more macro level, as the separation created between lawyers and legal services risks increasing the regulatory gap and, thereby, has wider implications on access to justice, lawyer-client privilege and legal service affordability.

The impact that certain technologies could have on the market is, therefore, not to be underestimated, and in considering which new technologies to invest in, practitioners ought to be alert to this distinction between supportive and substitutive technologies, as well as the changing framework of legal services regulation and how this may interplay with the more disruptive solutions out there.

Applying both models

Each model provides its own unique insight into the risks and opportunities within law and technology, and both may be used when examining novel technologies, as demonstrated in the table below.

That said, whilst relevant to the development and implementation of varying tech solutions, it remains to be seen whether these two models of categorisation will remain sufficient in capturing truly disruptive future technologies, or whether we will need to step back and reassess our perspective once again.

Leave a Comment